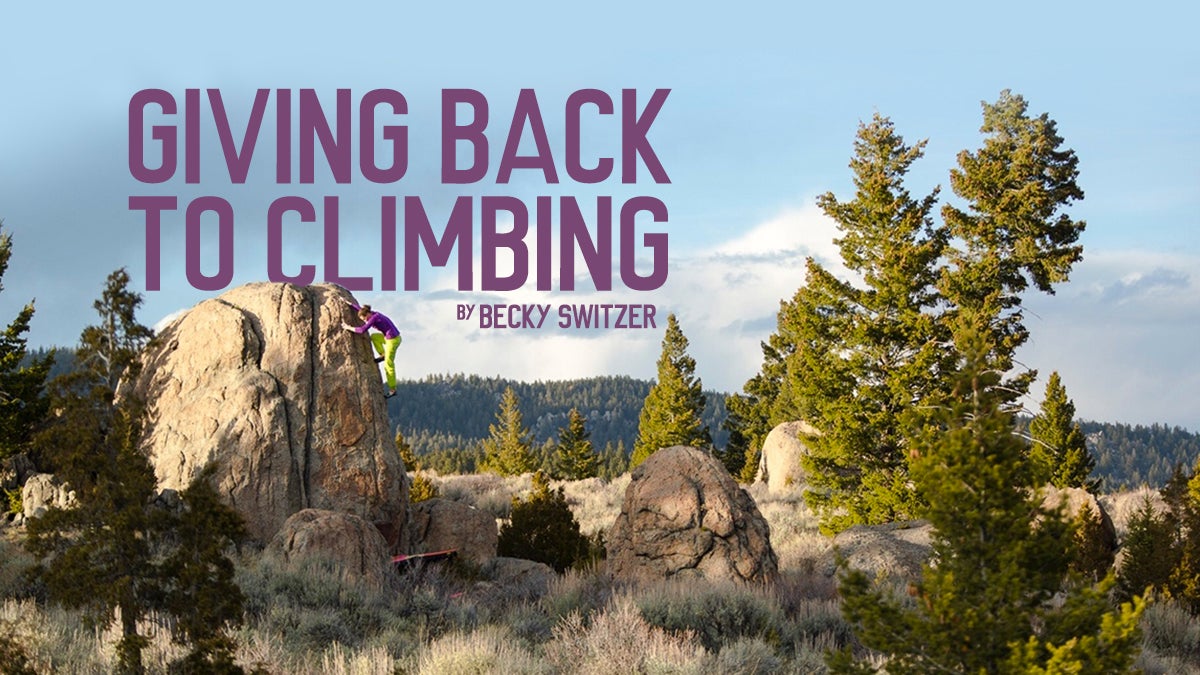

Giving Back to Climbing by Becky Switzer

Ambassador Feature by Becky Switzer

For those of us who have been climbing for longer than a decade, we can probably reminisce about how times have changed. It seems as if there is a new climbing gym popping up on every street corner. More of your friends are interested in climbing. You have to explain less and less why you spend so much money on gas for road trips. With the recent press surrounding the addition of climbing to the Olympics, the Dawn Wall ascents and the Freerider free solo, climbing is booming.

This leaves me to wonder about the younger generations of climbers coming up via climbing gyms, climbing teams, and the competition circuit. I had a stark realization recently that many of these young climbers have never climbed (or rarely climb) outside. Their entire perception of climbing has been based on pulling plastic, following tape colors, memorizing hold shapes and falling onto the plush carpeted padding of the gym floor. There used to be an automatic assumption that if you were a climber, you climb rocks, cliffs, boulders—things in nature. Today, I would be willing to bet that in many urban areas around the country, the perception of being a climber correlates with which gym you most often frequent.

I have mixed feelings about the popularity of indoor climbing. Of course, it is a great training tool, a safe place to learn ropes and systems, and a nice foul weather option. However, it would be a shame if the younger generation of climbers knew gym climbing as the only type of climbing, stifled in the confines of a building rather than exploring all the opportunities outdoor climbing can offer.

The big question is, then, where have the mentors gone? With the rise of climbing gyms, paired with the immense amount of information floating around on the internet, it appears as if mentors and the need for mentorship have morphed considerably. And while this role has changed, I would argue that it is still relevant and vital as ever to preserve climbing as a lifestyle, instead of an activity that gets put on a shelf after the excitement wears off and life’s priorities change.

As much as I’d love to say that climbing is all I do, all of the time, that statement wouldn’t be accurate. Over the past two years, I ran an organization that is dedicated to getting youth outside through climbing. This has become a massive focus for me (next to climbing and training) as I watch this sport, once considered to be on the fringe, become mainstream and supported by a large population of society. I’m encouraged by organizations such as this and the work that I see in pockets around the country—a concerted effort to get younger climbers out of the gym and into the outdoors.

It sounds like a simple task, but perhaps the role of mentorship needs to be delved into further to understand how important it is for climbing in today’s world. If we rewind to a time before bolted sport routes existed, we start to remember precisely why mentorship has been a staple of the climbing community. The most obvious reason was the technical challenge climbing presented; placing gear, avoiding loose rock, building anchors and general route finding. Without having the guidance of a more experienced climber, these tasks were not only daunting but were also life threatening if done incorrectly. This was a time when climbing information was gathered mainly through word of mouth and repeatedly practiced under the watchful eye of a mentor.

Aside from the technical skills that were passed on, mentors taught larger more persisting lessons. These lessons included resilience, conscientiousness, trust, and stewardship. Over time as mentors and mentees would climb together, the conglomeration of knowledge passed on would build a community and shape the activity of climbing into a lifestyle.

I had the opportunity to ask two segments of the climbing population about the role of mentorship in their climbing careers. Even though these two climbers are separated not only by age but also by life experience, their views of climbing mentorship run parallel. Here are their observations about having climbing mentors:

“Mentoring not only helped me dial in my understanding and practice of safe climbing, but it also provided guidance for the person I wanted to be and the life I wanted to live.”

“In the gym, you can sign a waiver and rely on the safety standards of the gym, but when you climb outside you need to accept the responsibility of your actions. Through mentorship, I gained the opportunity to learn how to make these decisions of being a responsible climber, and learning how to be a steward of the sport.”

Through these brief comments, the main thread develops—creating a lifestyle that perpetuates responsibility and advances climbing advocacy.

I suppose the final question is, what can be done to create and strengthen mentorship roles in your climbing community? Of course, the rock star thing to do would be to invite less experienced climbers out for a day of cragging. Even without making a conscious effort to talk technique or discuss beta, newer climbers are sponges and the power of observation will have them moving forward by leaps and bounds.

On a smaller scale, providing even the tiniest bit of guidance for a younger or less experienced climber can be incredibly simple. Instead of making elaborate plans, changing your career path or donating large sums of money to a climbing organization, mentoring another climber can be painless. Adopt someone (in a figurative sense). Help one person figure out the moves on a route or a boulder problem. Offer your advice about what climbs are best for a new climber wanting to break into the next grade. Or, if you’re on the other side of the coin and feeling like you need a climbing mentor, don’t be afraid to reach out and ask about that sandbagged trad route you’ve had your eye on. Having trouble making a clip at the crux of your project? Start a conversation with the next person who jumps on that climb. These interactions are the beginnings of mentoring, and although many conversations may end the very day they begin, the process has been put into motion, and the community has become a stronger and more welcoming place. Building relationships by relying on the knowledge of your climbing community help keep our sport rooted in a firm foundation. A foundation that was built on a mutual admiration for the mountains we climb, as well as respect for our fellow climbers.